17 articles

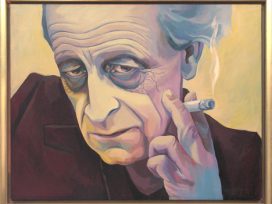

It is particularly fitting that, 50 years after the publication of Jean Amery’s Jenseits von Schuld und Sühne (1966), the jury highlights Adam Zagajewski’s essay A defence of ardour. Jenseits von Schuld und Sühne, translated into English as At the Mind’s Limits, is the book in which Jean Améry gives an account of his life as an intellectual who was captured while participating in the Belgian resistance against National Socialism, tortured and sent to Auschwitz [Jean Améry, At the Mind’s Limits, trans. Sidney Rosenfeld and Stella P. Rosenfeld, Indiana University Press, 1980. First published as Jenseits von Schuld und Sühne, Szczesny, 1966]. In the preface to the second edition, Améry writes about why “enlightenment” continues to inform his intellectual practice, and remains for him a “key word” that “embraces more than just logical deduction and empirical verification”.

That is why, now as well as earlier, I always proceed from the concrete event, but never become lost in it; rather I always take it as an occasion for reflections that extend beyond reasoning and the pleasure in logical argument to areas of thought that lie in an uncertain twilight and will remain therein, no matter how much I strive to attain the clarity necessary in order to lend them contour. […] For nothing is resolved, no conflict is settled, no remembering has become a mere memory. What happened, happened. But that it happened cannot be so easily accepted. I rebel: against my past, against history, and against a present that places the incomprehensible in the cold storage of history and thus falsifies it in a revolting way.

Améry concludes: “Enlightenment can properly fulfill its task only if it sets to work with passion”, and this is very much the spirit in which Zagajewksi’s “A defence of ardour” can be read today. Indeed, while the scars of totalitarianism in Europe and of the Cold War run deep in Améry’s writing and linger on in Zagajewksi’s essay, Zagajewski expresses the hope that “[p]erhaps, then, true ardour doesn’t divide; it unifies. And it leads neither to fanaticism nor to fundamentalism”. The jury too emphasize the affinity between Améry and Zagajewski, especially in terms of how both writers combine “a vigorous political alertness with an emphatic belief in art”. “A defence of ardour” forms a perfect complement to the current collection’s second essay by Zagajewski, The closing of an open society, in which he responds to current challenges in European cultural and political life.

These challenges constitute one of the central themes in an essay that Robert Menasse has contributed to the collection. In A brief history of the European future, he argues for a Europe of the regions, in which the region is the “logical political unit of administration in a post-national Europe”. Menasse, the Austrian writer and essayist who re-established the Jean Améry Prize in 2000 and chaired this year’s jury, recalls “the picture of the future drawn by the founders of the European project”; this he describes as “a masterwork of pragmatic reason in the spirit of the Enlightenment. […] Its political guidelines were human rights and, concretely, the human need for peace, social security, chances in life and opportunities for social participation. It was a project of life in dignity”. A timely reminder of the humanist roots of a European project to which the European people where absolutely central, a project founded in the aftermath of the destruction of European culture and civilization by nationalism. Indeed, a reminder that resonates with Améry’s own radical humanism. [Cf. Jean Améry, Radical Humanism: Selected Essays, edited and translated by Sidney Rosenfeld and Stella P. Rosenfeld, Indiana University Press, 1984.]

In the first of the texts by authors that Eurozine partner journals nominated for the Prize, the French essayist Marcel Cohen continues where Améry left off in At the Mind’s Limits. Cohen writes:

Since I did not experience the death camps and was, at the time, much too young to understand what was happening, I cannot speak of the Holocaust or of the Occupation. I only know about these events through books. And so I am in the position of being unable either to speak or to remain silent, even though I continue to maintain a passionate belief in the power of the written word.

Cohen’s latest book, Sur la scène intérieure (2013), consists of portraits of the family members he lost in the Holocaust. In his essay in the current collection, Cohen concurs with Samuel Beckett’s mid-twentieth-century remark: “To find a form that accommodates the mess, that is the task of the artist now”.

Literary and political forms merge in Ales Debeljak‘s essay The Yugoslav Atlantis. Here, the Slovenian critic, poet and essayist Debeljak expresses his fear that “that the European Union, like Yugoslavia, will prove a failure in the long run, unless it finds a way to prevent the dominance and supremacy of its most powerful member states”. Hence the continuous need to find ways of embracing difference without giving up the cultural tradition into which one was born and raised. Then, in East, or, the veins of this land, one of Poland’s leading writers and critics, Andrzej Stasiuk, revisits the territory near the Polish border with Belarus and Ukraine in which he grew up. Yet while reflecting upon the peaceful scenes he finds there, the memory of past conflicts and the presage of ones likely yet to come merge with Stasiuk’s recollections of his childhood.

Conflict remains a central theme in excerpts from historian Olena Stiazhkina‘s Donetsk Diary. Stiazhkina perceives the moment at which the Ukrainian parliament voted to remove Viktor Yanukovych from office as the end of the painful 23-year-long birth of a country. Finally, Ukraine was taking its destiny into its own hands; yet the descent of the country’s eastern regions into war all too quickly becomes the subject of Stiazhkina’s diary entries. Tropes of birth and death give way to an essay by Andrei Plesu on a theme that Jean Améry dedicated an entire book to: that of aging. [Jean Améry, On Aging: Revolt and Resignation, trans. John D. Barlow, Indiana University Press, 1984. First published as Über das Altern: Revolte und Resignation, Ernst Klett Verlag für Wissen und Bildung, 1968.] Plesu observes that, when reflecting on old age, Christian thinkers put a much greater emphasis on transcendence than Roman writers. This prompts him to consider how the dimension of transcendence might support a better understanding, and better use of, old age.

English essayist and author Kenan Malik argues in The human heart of sacred art that the humanist impulse not only liberated the sense of transcendence from the shackles of the sacred, it also transformed the idea of transcendence itself. Malik’s account of the humanization of the transcendent in art and literature ranges from Dante to Rothko. In an equally wide-ranging essay, French philosopher Olivier Remaud explores a rich vein of literature dealing with the theme of exile, from Ovid and Adelbert von Chamisso to Hannah Arendt and Siegfried Kracauer.

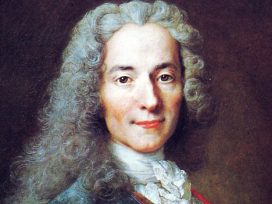

Norwegian literary critic Henning Hagerup grapples with the notion of the uncanny in European language and literature. He also considers how today Marxist thought “poses an unheimlich threat to the glorified, ahistorical arrogance of the capitalistic-neoliberal establishment”. Finally, Spanish philosopher and essayist Fernando Savater insists on the lasting significance of Voltaire’s objective to make each individual conscious of their intellectual independence. Indeed, without Voltaire, it would be impossible to conceive of either modern intellectuals or their enlightened audiences.

More about the Jean Améry Prize for European essay writing

The Jean Améry Prize honours essayists of the highest calibre who have contributed to the intellectual discourse in Europe, across borders. The Prize is awarded to essayists whose work has been at least partially translated into German or English, and who write in a similar vein to Jean Améry (without necessarily referring directly to Améry) – both in terms of style and of the agility of thought to which they give expression.

Recipients of the prize will have contributed to the intellectual discourse in Europe, across borders. The award is intended to heighten public awareness of the recipient’s oeuvre and to foster public debate. It is awarded every two years, with previous recipients including Dubravka Ugresic, Imre Kertész, Drago Jancar, Reinhard Merkel, Mathias Greffrath and Lothar Baier.

This year’s independent jury of literary scholars, writers and critics from different European regions was chaired by Robert Menasse and included: László Földényi (essayist, literary critic, translator, HU), Gila Lustiger (novelist, GER), Michael Krüger (publisher, writer, GER), Christina Weiss (former Cultural Minister, GER) and Claudio Magris (scholar, translator, writer, IT).

The Jean Améry Prize for European essay writing was founded in 1982 by Jean Améry’s widow Maria, together with his publishing house, Klett-Cotta. Up until 1991, it was awarded four times. In 2000, the Prize was re-established by the Austrian writer and essayist Robert Menasse together with the publisher Michael Klett, and awarded six times thereafter. In 2015, Allianz Cultural Foundation and Eurozine became partners of the prize, with a view to reinforcing its European dimension.

Nominations from the Eurozine network

Booksa.hr (Croatia):

Ales Debeljak, The Yugoslav Atlantis

Dilema veche (Romania):

Andrei Plesu, The art of aging in Christian life

Esprit (France):

Olivier Remaud, Exile and the Schlemihl complex

Krytyka (Ukraine):

Olena Stiazhkina, Country, war, love: Excerpts from the Donetsk Diary

Letras Libres (Spain):

Fernando Savater, Voltaire against the fanatics: The first modern intellectual

Lettera internazionale (Italy):

Marcel Cohen, The burden of the past

New Humanist (UK):

Kenan Malik, The human heart of sacred art

Res Publica Nowa (Poland):

Andrzej Stasiuk, East, or, the veins of this land

Vagant (Norway):

Henning Hagerup, Homely horror

Together with German publishing house Klett-Cotta and the Allianz Cultural Foundation, Eurozine is a partner of the Jean Améry Prize for European essay writing. The Prize honours essayists of the highest calibre who have contributed to the intellectual discourse in Europe, across borders.

Together with German publishing house Klett-Cotta and the Allianz Cultural Foundation, Eurozine is a partner of the Jean Améry Prize for European essay writing. The Prize honours essayists of the highest calibre who have contributed to the intellectual discourse in Europe, across borders.

The exile’s personal history can be compared to a shadow that he has lost and could never hope to recover, writes Olivier Remaud. Having acknowledged that life in exile tends to dehumanize, both inwardly and outwardly, Remaud explores a rich vein of literature dealing with the topic, from Ovid and Adelbert von Chamisso, to Hannah Arendt and Siegfried Kracauer.

It was Voltaire’s objective to make each individual conscious of their intellectual independence, writes Fernando Savater. Indeed, without Voltaire, it would be impossible to conceive of either modern intellectuals or their enlightened audiences.

In this excerpt from Andrzej Stasiuk’s latest book, one of Poland’s leading writers and critics explores what drove him to realize a lifelong dream, and strike out ever further eastwards, away from his childhood home. As Stasiuk remarks, he always was attracted to places “that lie at the end of the line, spaces from which you can only ever return”.

Just weeks after Ukraine’s parliament voted to remove Viktor Yanukovych from office, the country’s eastern regions descended into a senseless war, marking a grave new low in relations with Russia. Historian Olena Stiazhkina reflects powerfully on how the conflict has compromised Ukraine’s attempts to take its destiny into its own hands.

One almost wonders what Christianity has added to Roman writers’ reflections on old age, writes Andrei Plesu. The answer: a much greater emphasis on transcendence. But how might the dimension of transcendence contribute to a better understanding and use of old age?

In honour of Adam Zagajewski being awarded the 2016 Jean Améry Prize for European essay writing, Eurozine publishes Zagajewski’s defence of ardour. That is, true ardour, which doesn’t divide but unifies; and leads neither to fanaticism nor to fundamentalism.

As the struggle between democracy and a dream of some kind of return to the past deepens in Europe, Adam Zagajewksi contemplates the passage between ideas and action in the real world, wherein lies the old European – and not only European – wound.

Responding to the appalling violence that the machineries of war and economics unleashed during the twentieth century, Marcel Cohen concurs with Samuel Beckett’s mid-century remark: “To find a form that accommodates the mess, that is the task of the artist now”. Based on a speech first delivered in 1998, Cohen’s essay remains hugely relevant today.

Like Yugoslavia, the European Union may well prove a failure in the long run, unless it can prevent the dominance of its most powerful member states. Hence the continuous need to find ways of embracing difference without giving up the cultural tradition in which one was born and raised.

The sooner Europe gets used to a future without the nation-state, the better, writes Robert Menasse. Amnesia about what the unification project originally meant is causing a catastrophic lack of imagination about where it is heading.

The humanist impulse not only liberated the sense of transcendence from the shackles of the sacred, it also transformed the idea of transcendence itself. Kenan Malik on the humanization of the transcendent in art and literature, from Dante to Rothko.