Standing up for your country’s social and ecological wellbeing can be a desperately meaningful undertaking when deep-seated corruption lies behind the struggle: the exodus of many Romanian protesters attests to the high personal risks that have compounded solidarity both at home and abroad over decades of action.

It was the first in a series of major protest movements, which, over the past eight years, have set about renegotiating the relationship between the Romanian public and their politicians and have demanded and enabled the rise of new forces in the political sphere.

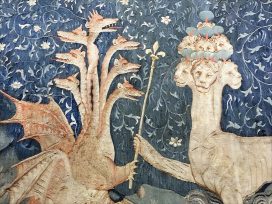

Photo by Danny Williams, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Rosia Montana protests

In 2013, the Romanian government proposed a law to allow a Canadian company, Gabriel Resources, to extract an estimated 800-4000 tonnes of gold and around 1500 tonnes of silver at Rosia Montana, using around 40 tonnes of cyanide per day.

The government, dominated by the Social Democrats and led by Prime Minister Victor Ponta, argued that the region needed the project to escape poverty. However, the region’s impoverishment was the result of governmental industrial policy, which had declared the region a mono-industrial mining area, preventing alternative types of development for Rosia Montana.

Exploiting the mine entailed destroying four forested mountains, contaminating several rivers, destroying several fragile ecosystems, and ruining over 900 historical buildings. It also required damming part of a river valley to hold 250 million tons of cyanide-laced waste.

The proposals triggered an unprecedented wave of socio-environmental protests demanding that the law be withdrawn and the project stopped. Instead, the protesters wanted Rosia Montana to become an ecotourism hub and a recognised UNESCO heritage site, due to its well-preserved Roman mines.

Taking place weekly between September 2013 and January 2014, the demonstrations attracted up to 200,000 demonstrators in 50 Romanian cities and 30 cities abroad. The largest single protest saw 20,000 people gather in Bucharest. While people were motivated by a combination of reasons, the unifying ones were anti-corruption and environmental protection.

Rosia Montana was a historical moment in the country. It opened the gateway to a overhaul of the relationship between the government and the population: people reclaimed their power and understood that they held influence over political decisions and could call for accountability and transparency about decisions taken against the country’s best interests. In doing so, citizens took the first steps in relaunching the demand for long-term change and establishing a functional democracy in Romania, last claimed in the early 1990s.

Photo by Silviu filip, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The 1990-1991 “Mineriade” protests

Known as the Mineriade, Romania’s early mass-scale post-communist protests ended in horrendous violence. In June 1990, young Romanians, mostly high-school and university students, professors, intellectuals and other professionals, wanting a democratic future and disappointed by the direction their country was taking, demanded that communists and former communists, including then President Ion Iliescu, the first president of the post-communist era, be excluded from public office. The protested saw Iliescu’s government, consisting mainly of former communists, as implementing democratic reforms either too slowly or not at all.

To restore order in Bucharest and save a so-called threatened democratic regime, Iliescu called on the staunchly loyal mine workers from the Jiu Valley to come to the capital and repress the protests.

Repress they did. Although official figures at the time indicated four fatalities and hundreds of injured, more recent estimates suggest that the actual number of people injured was above 1300, with around the same number being arrested for political reasons.

These violent episodes, most of which took place in 1990 and 1991, created a long-lasting trauma that built on the existing fear of violent repression under communism. The fear of taking to the streets for political protest would take decades to overcome. The clashes also pitted the working class against the intellectual class.

The Mineriade helped drive the first wave of post-communist emigration from the country. Tens of thousands of students and professionals sought new horizons in western Europe, the United Kingdom, and the United States, which were still accepting Romanians as political refugees at the time. The exodus had incalculable social and economic consequences for Romania, as driven, educated people with aspirations for their country left. Unlike subsequent waves of emigrants, many never returned, taking their families with them and assimilating within their receiving communities. In this sense, it was truly a lost generation for Romania.

Parallels and departures

For the Rosia Montana protests, the initial fear was that there would be violent repression from the government, like during the Mineriade, because of the extremely high stakes of the mining project. At first, politicians refused to engage the protesters’ demands, even when tens of thousands were on the streets. Then, as the demonstrators kept showing up week after the week, politicians moved to insult them. Prime Minister Ponta called them “anarchists” and “good for nothing hipsters.” A similar language of depreciation had been used during the Mineriade. Iliescu had called the protesters “hooligans” and suggested that fascists groups had infiltrated the protests to seize power.

Just like with the early 1990s protests, the Rosia Montana protesters were predominantly young, students, activists, artists, and intellectuals from across the political spectrum. While there were some incidents of pepper spraying and some arrests, for the most part the protests faced little violence. This helped protesters overcome the fear of violent repression internalised during the last major protests of the post-communist era.

The substantial difference in the governmental response stems to a large extent from the very different European environment in 2013 compared to the early 1990s. Romania had entered the European Union in 2007 and breaches of the rule of law could henceforth be reprimanded by the European Commission. Responding with violence to peaceful protesters would have cast the Romanian government in a negative light on the European stage. As a result, the Rosia Montana protesters gradually understood that the government could not and would not repress them violently.

The diaspora played a significant role in the protests. In cities across Europe and the United States, people united in front of embassies and government to demand that the project be stopped. By 2013, there were around 2.7–3.5 million Romanians living in Western Europe, mostly in Spain, Italy, and Germany. Many of them retained ties to Romania through family connections, sending remittances, and voting – often with a significant impact. In the 2009 presidential election, the diaspora vote ultimately decided the winner.

A historic win

Protests against Rosia Montana gold exploatation in Timisoara, on September 22, 2013 (Now or never)

Photo by Ady777, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

When the Rosia Montana protests started in September 2013, nearly no one in Romania believed that they would succeed. There had never previously been an instance in post-communist Romania of the people emerging victorious from a confrontation with the Romanian government.

This time around, however, the demonstrators came with unprecedented resoluteness driven by years of disregard from a corrupt and greedy political elite that did not prioritise the country’s best interests nor its citizens’ wishes. After they made themselves impossible to ignore, the Parliament rejected the law proposed on Rosia Montana in June 2014.

This peaceful citizen victory helped reshape the political landscape in Romania. People found strength in numbers and realised that change could be achieved through persistent action. Politicians also understood that this was not the population of 20 years ago, but rather a younger generation, determined to hold their politicians to account.

There was also a sense of deepened solidarity between the diaspora and those in the country, not perceived before. The diaspora showed that it was not there just to send remittances, but also to fight alongside the population for causes that mattered for Romania’s future.

The Rosia Montana victory was followed by a raft of political and environmental protests, such as the one opposing parliamentary immunity in 2015 and the 2014 presidential elections’ diaspora voting bloc.

The Colectiv protests

The next crucial protest movement surrounded the Colectiv nightclub fire on 30 October 2015. The fire resulted in the death of over 60 people, mostly from burns and chemical smoke inhalation, and injured 150 others, dozens of whom were left disabled. It was the deadliest fire in the country’s history, caused by a lack of appropriate safety measures. The club had been given an operating license by the local mayor’s office without a fire safety permit. The acoustic foam on the walls ignited from pyrotechnics, causing a human stampede toward the single-door exit.

Many could have been saved, if it had not been for the systemic flaws of the medical system in Romania, left to decay by the Romanian political class during the post-communist era. The hospital care that the injured receive was inadequate. Following the fire, the government insisted that it had the capacity to treat the victims, even though the country had few burns units. Patients were only transferred abroad for treatment around eight days after the fire, which, for some, was already too late.

For others, suffering from non-life-threatening burns, staying in Romanian hospitals proved to be fatal, as they went on to die from bacterial infections due to diluted disinfectants. According to an independent analysis, some active ingredients had been diluted down to just 1 per cent against the 12 per cent recommended concentration.

This system had been set in place under the watchful gaze of mobsters running state-run hospitals as political appointees, not medical experts. Their sole loyalty was to their political patrons, with whom they shared graft money.

Outraged by the situation, on 3 November 2015, around 15,000 gathered to protest in front of the Romanian government headquarters, calling for the resignation of Prime Minister Victor Ponta, who had survived Rosia Montana, and of the local mayor who had granted the nightclub’s licence.

The following morning, the Ponta government resigned. As the first sitting premier to stand trial for corruption amid a tax fraud scandal, he was already under substantial pressure. The mayor also announced his resignation.

Nevertheless, the protesters were not appeased: they continued to gather in the days that followed, with 35,000 people demonstrating in Bucharest and 10,000 in Timisoara, among other cities, calling for a profound overhaul of the country’s politics. Solidarity protests were again held in the diaspora, in cities including London, Paris and Madrid.

It was only on the seventh day, after Klaus Iohannis, Romania’s President, held consultations with street representatives and personally visited the main protest area that the protests stopped.

The rise of new political parties

While the Rosia Montana protests dissipated following the halting of the mining project, reaching their primary objective was not enough for the Colectiv protests. Continued protests signalled that Romanians were no longer satisfied with short-term fixes. They had understood that the real stake of their protests was the country’s future. Just like their predecessors 25 years earlier at the 1990-1991 protests, they wanted a new political class, capable of fulfilling their country’s democratic promise, and they wanted it immediately.

In 2015, the protesters’ determination was partly emboldened by a heightened awareness of high-level corruption over the past two years. Under the new leadership of Laura Codruta Kovesi, the National Anticorruption Directorate (DNA) had just launched a crackdown on political elites and authorities. In 2014 alone, the directorate indicted over 1,130 figures, including politicians, prosecutors, and businessmen. In 2015, cases were filed against an additional 1,250 high-level politicians, including Victor Ponta, ministers, and parliamentarians. The forms of corruption that particularly incensed people included tax evasion, procurement deals involving substantial sums of EU money, and exercising undue influence over the judiciary.

As a result of the protests, then-President Klaus Iohannis selected Dacian Cioloș, a former Romanian Minister of Agriculture and European Commissioner, to form a cabinet of technocrats in November 2015. Cioloș himself, though previously involved in politics, remained an independent.

Further capitalising on this demand for change, in 2018, Cioloș created a new centre-right political party, called the Freedom, Unity and Solidarity Party (PLUS). His party’s creation had been preceded by the launch, in 2016, of another centre-right party, Save Romania Union (USR), as an alternative for people disappointed by the political elite. USR considered itself centrist on social issues and centre-right on economic issues. Many members had no previous political background and had diverse profiles, including ecologists, neoliberals and activists. The party placed anti-corruption at the core of its agenda, lending its support to the civic campaign “No Convicts in Public Office”, in 2018.

Headquarters of the Association of Victims of the Mineriad, Bucharest, Romania Photo by Joe Mabel, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In 2019, PLUS and USR joined forces to run together in the European Parliament elections, before ultimately merging in 2021. USR-PLUS is currently part of the coalition leading Romania, alongside the National Liberal Party (PNL), and the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania.

The long wait for a Green breakthrough

The Green presence at the political level in Romania remains very weak and fragmented. A Green party has existed since 2005, but has so far failed to produce any prominent leading figures. It was preceded by the Ecologist Federation of Romania, created in 1990.

The Greens participated in the Rosia Montana and shale gas protests and made statements opposing both projects. However, they played a minor, indecisive role, instead of using the movement as a platform to propel their ideas to the forefront of politics, especially as the youthful, urban, intellectual audience was demanding change.

An important factor hampering the rise of the Greens is the fact that the Left in Romania is still dominated by the Social Democrats (PSD) and has been for the past three decades. Despite being mired in severe corruption scandals, in the 2020 parliamentary elections, the PSD still won 29 per cent of the votes, followed by PNL at 25 per cent and USR-PLUS at 15 per cent.

The PSD’s continued position as a monolithic left-wing force sets Romania apart from other Eastern European cases, where green actors have begun to secure power, at least at the local level. In Hungary, for instance, the fragmentation of the Left after the Hungarian Socialist Party, a successor of the Communist Party, suffered defeat in the 2010 parliamentary elections, opened the door to the rise of several other left-wing groups. Most significant among them was the Democratic Coalition (DK), which has become a key opposition party in Hungary. The erosion of the traditional Left also created space for the rise of the country’s two main Green parties: Dialogue for Hungary (PM) and Politics Can Be Different (LMP). Having a strong new socialist party, such as DK, available and willing to form a coalition, played a key role in getting the opposition candidate for prime minister, Gergely Karácsony, elected as the mayor of Budapest in 2019.

The overall context is similar for the recent victory of the Zagreb city assembly and mayoral elections in Croatia in May 2021: the Social Democratic Party had been losing credibility among the traditionally left-leaning Zagreb electorate. This contributed to strengthening the position of the Green-Left Coalition, composed of smaller left-wing and Green parties, ultimately leading to its recent win.

Such a left-wing coalition is virtually unfathomable for the Greens in Romania, given the enduring popularity and unity of the PSD. Understanding this reality, the nascent parties forming in Romania knew they needed to clearly distinguish themselves from the PSD, while positioning themselves as anti-system initiatives and catering to the protests’ youthful, urban, intellectual audience. The obvious choice was centre-right.

USR and PLUS have adopted green ideas, such as developing the recycling and circular economy sectors, mass reforestation, and decarbonisation. For the Greens, this means that they now need to set themselves apart not only from PSD, but also from these new centre-right parties. This remains possible, as these parties also promote non-green policies, such as nuclear energy and Black Sea gas extraction.

As it stands though, the Romanian Greens first and foremost need an internal overhaul, before reshaping their agendas and policies. The party remains riddled with conflict between members and dominated by middle-aged men. Whether the Green party in its current form will succeed in implementing the changes needed or whether a new green or progressive party will need to take over remains to be seen.

An unsatisfied appetite for change

Popular discontent with USR-PLUS is already building. Having run a campaign on anti-corruption, they are now backpaddling, claiming that corruption will not represent a problem when it comes to the absorption of EU funds based on the national recovery and resilience plan. Meanwhile, the Romanian anti-fraud office has called on prosecutors to investigate Dan Barna, USR’s President since 2017, for alleged misuse of EU funds in several projects.

The door for change is still open, as evidenced by the phenomenal rise of the extreme-right party, Alliance for the Union of Romanians, which gained 9 percent of the vote at the parliamentary elections of 2020, despite having only being created in 2019. As Romania has not witnessed successful far-right movements in recent times, this is a particularly worrisome trend.

The protest wave that began in 2013 has little by little reclaimed the space for the Romanian public to express the unfulfilled political demands for change and democracy of their precursors who took to the streets in Romania’s early post-communist days. This makes for an effervescent time in Romanian history, full of undeniable promise and perils ahead. There are greater opportunities than ever for new actors, including the Greens, to take the stage and shape Romania’s future.

This article was first published in the Green European Journal on 10 August 2021.

Published 22 November 2021

Original in English

First published by Green European Journal

Contributed by Green European Journal © Raluca Besliu / Green European Journal / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

The difference between knowing from distance that war is being waged and living that reality couldn’t be more extreme. But can awareness of multiple repercussions turn protective disassociation from violence into active solidarity? ‘The Most Documented War’ symposium in Lviv, Ukraine, provides valuable pointers regarding engagement and responsibility.

Tracing responsibility for honeybee losses in rural Ukraine points to farmers and pesticide-treated rapeseed fields. But whose practices really lie behind the short-term bid to increase crop productivity? And what do the historic uses of agrochemicals tell us about their current weaponization?