17 articles

Twenty years after 1989, most former communist states in central and eastern Europe are members of the EU. Yet the transition from closed to open societies is far from “complete”.

Fierce debates rage over lustration and information surfacing from secret police archives, over corruption inherited from communist power structures, and over dominant representations of the communist past.

Clearly, 1989 is not only an historic moment of liberation, but also a political and social dilemma for the present day.

Nothing was inevitable. If the Soviet Union had wanted, it could have easily stopped the process that led to the dissolution of the Communist bloc in 1989 – says Professor Mark Kramer, director of the Cold War Studies Program at Harvard University. As he sees it, the changes were ultimately caused by three factors, neither sufficient in itself: the fundamental change in Soviet policy reflected in Mikhail Gorbachev’s commitment to promote far-reaching reform and avoid the use of violence in Eastern Europe, the willingness of millions of ordinary people to go out onto the streets to demand freedom, and the rapid demoralization of hardline East European leaders as they realized that the Soviet Union would not come to their aid against internal rebellion.

How far did the West support the transformation of eastern Europe in 1989? Documents recently released from the Hungarian archives reveal how western leaders, without exception, deferred to the Soviet Union at the time, writes László Borhi. The threat of regional chaos and residual fear of German hegemony meant an overwhelming support for preserving the status quo as the events of 1989 unfolded.

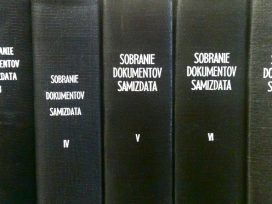

“A person comes in, protests just like you, then shouts and rants, and then, when finally shown the piece of paper that was signed when they were on military service, they crumple.”

The Czech communist party might be an anachronism, but to ostracize it only prolongs its existence. Whether irrational or calculated, anti-communism in the Czech Republic distracts from more pressing problems, writes Marek Seckar.

The notion of abandoning the East for the sake of a brighter western dominates the Polish memory of ’89, writes Wojciech Przybylski. Renewed debate among the born-free generation about the period of change would foster a more individual cultural identity

After 1989, uncensored editions of many classics of contemporary eastern European literature became available, and numerous authors were discovered for the first time in the West. Meanwhile, a younger generation of writers, their imaginations liberated by events, were quick to respond to the new appetite for understanding the communist past. Katharina Raabe, editor for eastern European literature at Suhrkamp Verlag, surveys some of the most important of these authors and describes German publishers’ role in bringing them to western readers.

“Like the champagne from the bottles in Prague, that’s how the tears came rolling from my eyes! I’m tellin’ ya, if a Czechoslovak had been within reach, I’d’ve licked his ass clean!” A tough-talking Magyar remembers the stirrings of neighbourly affection in ’89.

“It is an unnatural but positive development when democracy trains people to believe that, overall, it is better to let the bastard speak.” Former Solidarity activist and journalist Konstanty Gebert talks to Irena Maryniak about censorship post-’89 and anti-Semitism in Poland today.

Two books dealing with the state security apparatus in communist Hungary emphasize the extent to which its members, from informants and their handlers up to high-ranking politicians, were subordinate to the Communist Party hierarchy. Clearly, a much wider circle of people than the network of agents were responsible for the disadvantages, and even vilification, suffered by thousands of people.

No one in eastern central Europe suspected that once the fight for independence was won, democracy would become a parody of itself, writes Tomas Kavaliauskas. Open disrespect for the public jars with the ideals of the Baltic Way that existed before and after 1989.

Twenty years ago, the velvet revolutions swept communism from eastern Europe. On the other side of the globe, the Chinese government was cracking down on anyone who dared to speak out against the regime, with reprisals culminating in the Tiananmen Square Massacre on 4 June. In the twenty years since Tiananmen, writes Martin Hala, China has risen from the ashes by engaging the West economically and by manufacturing domestic, “patriotic” consent. But as the economic crisis deepens, writes Hala, these achievements might not be sufficient to make the “rising dragon” immune to history.

In Romania, the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives has been rendered toothless by political interference and its moral authority drained, writes Mircea Vasilescu. Meanwhile, former communist functionaries, in new democratic guise, still purport to be protecting “national interest”.

The dissident generation of the 1970s and 1980s produced a body of work unprecedented in Czech history, says Martin Simecka. Yet it is precisely the monumentality of this generation’s legacy that prevents the interpretation of the communist past going beyond self-diagnosis.

Jaroslaw Kuisz comments on two iconic Polish films that show the brutality, fear and loneliness that have accompanied the new political order. In Wladislaw Pasikowski’s “Psy” (Pigs, 1992) a former security service agent turned respectable post-communist policeman resolves to avenge the death of three colleagues. And in Krzysztof Krauze’s “Dlug” (Debt, 1999), two young businessmen, trapped into life as mobsters, commit murder, then confess.

“When in opposition, they do not comport themselves as the opposition to a democratically elected government. When they become the governing party, they pursue the same paternalistic, populist political game.” Agnes Heller’s damning indictment of Hungarian politicians twenty years after 1989.