There have been a number of historic elections in post-war Germany, though few deserve the epithet better than the latest one. The results signal the resurrection of the SPD, something that until very recently seemed highly unlikely. But they also stand for a missed chance for the Greens to gain power and shape politics. More momentous still is the collapse of the CDU/CSU as the last intact People’s Party; in this respect the elections mark the end of the Merkel Republic, in which everything revolved around the Union as centre of power. Finally, the results introduce the need for new, more complex political constellations, bringing the old Federal Republic to a definitive end.

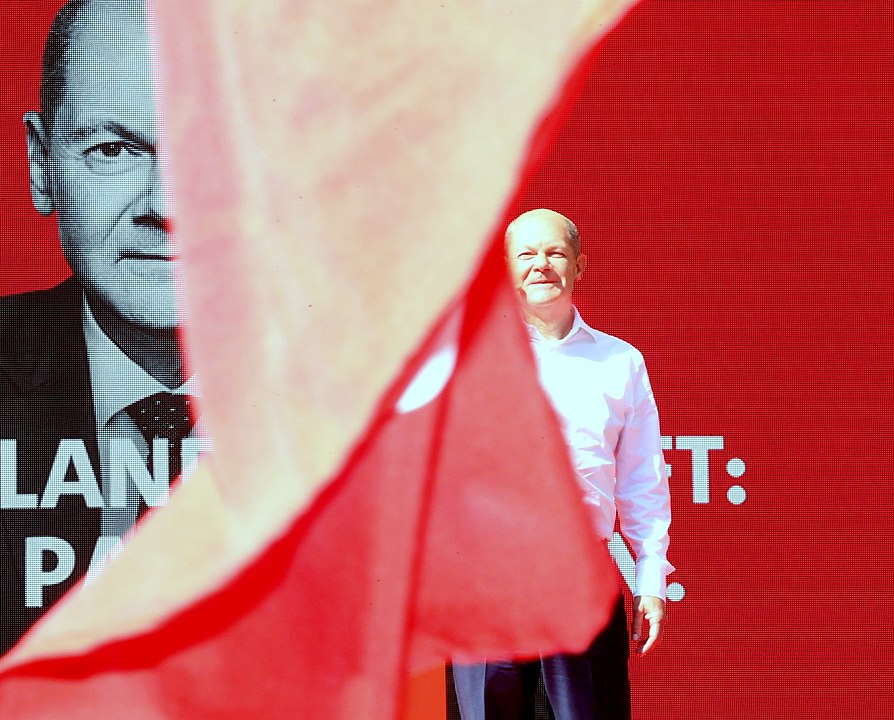

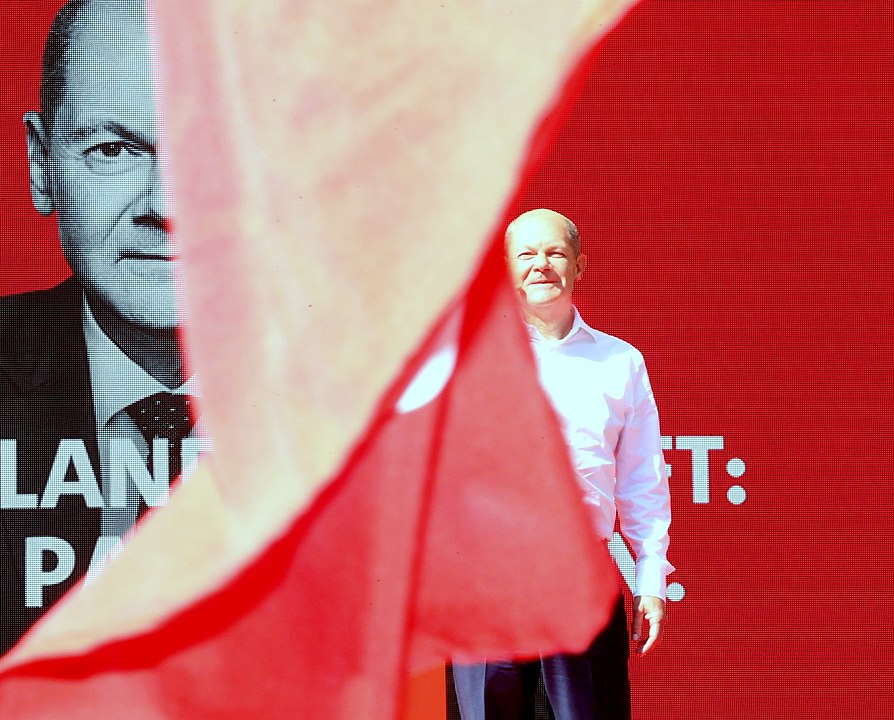

This election had one winner: the Social Democratic Party of Germany. The defining image of election night was Olaf Scholz flanked by the two winners of the state elections, Franziska Giffey (Berlin) and Manuela Schwesig (Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania). After gaining its worst ever result in 2017, the SPD had atrophied into a northwest German regional party. Its victory in 2021 is perhaps the most astonishing political comeback in recent history.

But the party has above all to thank its opponents for its victory. More so than in any previous election, this one was decided by the losers. It was not the strength of the SPD but the weakness of the Greens and CDU/CSU that liberated the SPD from its agony. A year ago, the party was still languishing at 17%, a full 20% behind the Union and also far behind the Greens, although Scholz had already been appointed SPD candidate.

It looked like the time had come for CDU/CSU–Green. It was only thanks to massive mistakes by both parties that Scholz’s plan succeeded. From the start, he and his team had wagered that the vacuum left by Merkel’s departure could best be filled by the finance minister. Merkel’s sixteen-year dominance meant that these elections were focused almost exclusively on who would succeed her at the top. For the first time in the history of the Federal Republic, the choice of chancellor overrode party political preferences.

The first casualty of this development were the Greens. Although the party achieved its best-ever result at the federal level and outperformed its 2017 figure by a long way, the outcome was a bitter disappointment. The Greens had two central goals: first, to win over 20% of the vote and, second, to replace the SPD as hegemonic force of the centre left, if not to win outright. They failed on both scores and in doing so have missed an opportunity to implement a far-reaching climate policy. In a three-way coalition, they will now encounter massive resistance. ‘Ready, because you are’ was the slogan of the Green Party campaign. But the great majority of voters were not ready to elect a candidate with no experience of government on a ticket of radical renewal.

Photo by Michael Lucan, Lizenz: CC-BY-SA 3.0 de, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE, via Wikimedia Commons

The Union implodes

But the collapse of the CDU/CSU was incomparably more dramatic. Armin Laschet led the CDU/CSU to its worst result ever – even worse than in 1949, when Konrad Adenauer won with 31% against the charismatic SPD leader Kurt Schumacher and ten other parties. Worse still for the Union is that by dropping beneath the 30% threshold, it can no longer form a classic two-way coalition with a smaller party.

The reason for this unprecedented collapse was the conflict between Markus Söder and Armin Laschet, which had caused the CDU/CSU machinery to lose its instinct for power. Part of the CDU leadership, led by Wolfgang Schäuble, hubristically believed that victory was assured and that the Union could do without a popular tribune such as Söder, even though his approval ratings were consistently higher than Scholz’s. Ironically, it was weakness of the SPD that led the CDU leadership to assume that the Union would win regardless of whose face was on the campaign posters. The CDU was punished for its complacency by none other than Söder, who proved a more formidable opponent than anyone from another party.

Laschet’s candidacy thus became the greatest political experiment in the history of the party of ‘no experiments’ (Adenauer). He proved unable to transfer the trust in the party accumulated by Angela Merkel onto himself as her natural successor, either as chancellor candidate or as party chairman. During the pandemic, Merkel’s authority had already shifted to Söder. When he dropped out of the contest, that authority went to Olaf Sholz. By the end, Scholz was acting more like Merkel than Laschet.

The Union then emulated the SPD’s unprecedented feat of rapid implosion. Its collapse signals the downfall of probably the most important remaining people’s party in Europe – and for the necessity of a completely new way of governing in Germany. Given the lack of appetite on both sides for another Grand Coalition, the only alternative is a three-way coalition.

Scholz’s dilemma

After the Left Party almost failed to enter the Bundestag, only two such coalitions are possible: the ‘traffic light’ coalition (SPD, Greens, FDP) and the ‘Jamaica’ coalition (CDU, Greens, FDP). The former is most likely at this point. However, there are major differences between the partners. At present it is very hard to see how a compromise can be found between the core SPD–Green demand for a minimum wage of €12, higher taxes and new borrowing, and the FDP’s refusal of all three. Nevertheless, Scholz clearly favours this constellation over ‘Red2Green’, had that been an option. After all, his success reflects voters’ desire not for a radical break but merely a partial corrective to Merkel’s inoffensive politics of status-quo.

Herein lies the greatest dilemma of these elections. Anything short of radical social-ecological change will mean that four crucial years for climate policy will have been wasted. Germany needs a stable, resolute and efficient coalition able to deliver policy in the face of opposition from an increasingly recalcitrant ‘civil society’. However, the three parties in question seem far from being able to do this.

The country finds itself in a completely unfamiliar position. In a three-way constellation, a chancellor whose party won significantly less than 30% will come up against massive centrifugal forces. The result will be that the second-row players, especially the two vice chancellors, will assume greater importance. In the best case, the Greens and the FDP will complement one another. In the worst case – and the more likely one – they will cancel one another out. What you then get is deadlock, and that in the face of maximal problems and future crises. Ultimately, we all risk being the losers of this election.

Given these immense challenges, the question of a minority government inevitably arises again. An instrument long used in other countries, in Germany it has traditionally been avoided at all costs. Its core would be an SPD–Green government under Olaf Scholz, who would need to organize parliamentary majorities on the left and the right of the party spectrum.

This would lead to huge politicization and a more substantive political debate. It would require the kind of passionate, authoritative and persuasive chancellor that the Federal Republic has seen on occasions in the past. But try as he might, Olaf Scholz is unlikely to become a Helmut Schmidt, let alone a Willy Brandt. If Scholz resembles anyone, then it is his predecessor. Which is why, unfortunately, he is unlikely to wager the experiment of a minority government.

Whatever the case, one thing is certain: the motto of the SPD campaign, ‘it depends on the chancellor’ will be as crucial after the election as it was before. The coalition talks will offer a glimpse of what to expect – and whether the next four years will be time lost, or time spent wisely, despite all the difficulties.