Is France really moving right?

Claims that the French electorate has moved right are based on faulty evidence. Because dealignment primarily affects the left, support for redistribution and acceptance of diversity are not reflected in the polls. But the real problem for French politics begins in the voting booth.

Until the beginning of the Ukraine war, voting intentions in the French presidential elections on 10 April seemed to have stabilized. Week after week, polls were showing that the best-placed leftwing candidate, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, was stuck at around 10% of votes. All the leftwing candidates combined amounted to around a quarter of intended votes, or 30% at the highest. On the opposing side, Emmanuel Macron was significantly ahead, with about a quarter of votes, while Nathalie Pécresse, the candidate of Les Républicains (LR), wavered around 15% or slightly higher. On the far right, Marine Le Pen and Éric Zemmour were together outperforming all the leftwing candidates combined.

Since late February, Macron has seen a surge of support, bringing him up to over 30%. This is at the expense of Pécresse, in particular, whose support has dropped to around 12%. Polls show a slight dip for Zemmour, too, although Le Pen, despite her embarrassment over Russia, remains at around 17%. With the exception of Mélenchon, whose support has increased by a couple of points to bring him level with Zemmour, the Left candidates flounder at 5% or less.

France would therefore seem to have moved to the right. However, this rightward shift is by no means proven, much as interested parties in politics, academia and the media might desire it. Some signs of a shift do exist, but other indicators point in a different direction, particularly when we measure support for redistribution or tolerance of diversity. More than anything else, it seems we are seeing a dealignment between citizens and party politics, and that this dealignment affects the Right less than it does the Left. What has been called a rightward shift is primarily caused by the fact that the Right, although weakened, is not as weakened as the Left.

A view over Belleville, the historically working class and multi-ethnic district of Paris. Photo by KimonBerlin via Wikimedia Commons

Polling and the rightward shift

Polling has become a major factor in 2021–2022, with the ‘horse race’ one of the dominant ways election campaigns are covered. The number of polls relating to the presidential elections is constantly growing: from 193 in 2002 to 293 in 2007 to 560 in 2017, according to the Survey Commission. The increase is due to the reduction in the cost and time needed to carry out internet polls. This is not new, nor particular to France. But it has certain effects.

First, there is the problem in that we do not know who the respondents are. Luc Bronner at Le Monde was able to respond to two hundred polls, claiming variously to be male or female, between nineteen and seventy-three years old, and a white-collar employee, member of the liberal professions or retiree.1 But beyond this question of reliability, it seems those who respond on the internet tend to have a political bias, in particular towards the right.

We are often told that online polling gauges opinion more accurately. Respondents feel free from ‘political correctness’ when there is no one asking them questions directly. Online pollsters note that, in contrast to telephone and face-to-face polls, they don’t need to ‘correct’ the vote in favour of the Rassemblement national (RN). That online polling overestimates the Right and far Right was clearly demonstrated in the run-up to the 2021 regional elections, when the RN vote was overestimated by between 4 and 9 points. In Occitanie, the RN had been polling at 31%, in front of the list led by the leftwing incumbent Carole Delga (29%). Ultimately, Delga secured 39.5% of votes and her RN rival 22%.

Second, voting intentions are generally calculated based on people who are certain to vote, and this subsection of society is politically and socioeconomically skewed. According to a survey carried out in October 2021 by the pollsters Cluster 17, 76% of over 65s said they would definitely vote, compared to 65% of 35–49s, 61% of 25–34s, and 57% of 18–24s.2 Moreover, 70% of the higher social classes were politically mobilized, compared to 61% of white-collar employees and 58% of manual workers and the economically inactive (not including retired).

The voting intentions measured by polling are, above all, a reflection of a subsection of French society, one which currently leans to the right. Among voters who self-identify as being on the right, 66% are certain to vote and 21% will ‘probably’ or ‘definitely’ abstain. For those identifying on the left, the figures are 57% and 32% (figures from end of November 2021). In other words, voting preferences lean further to the left if we include those who are less certain to vote. Among people who preferred Jean-Luc Mélenchon, only 55% were sure to vote, compared to 70% of supporters of Éric Zemmour, 69% of supporters of Pécresse, and 67% of supporters of Macron. Overall voting intentions therefore tilt rightward, but via a double selection bias towards the Right: first because of the use of the internet and, second, because leftwing voters are less engaged.

The richer and the older, the better represented

Some commentators endorse the idea of a rightward shift based on the results of the municipal and regional elections in 2020 and 2021 respectively, when 61% of towns and cities with populations over 20,000 were held by the Right, along with more than two-thirds of départements and seven of the twelve metropolitan regions. These facts cannot be contested. But the conclusions that have been drawn from them are debatable.

Are French people who exercise their right to vote representative of the electorate as a whole? This old question takes on even greater significance as abstention rates rise. The lower classes, who represent a ‘social majority,’ are on their way to becoming an ‘electoral minority.’3 In-work manual workers represent 12% of France’s population and 19% of the economically active population, while white-collar employees represent 12.5% of the population and 20.5% of the economically active. However, the former make up only 8% of voters and the latter 9%. The only groups who were represented among voters better than among the population at large were managers, who made up 14% of the population but 17% of voters, and retirees, who made up 32.5% of the population but 36.5% of voters.

As well as overrepresenting the upper classes, the 2021 elections were also dominated by older people. On the basis of various polls, people over 65 were 1.3 to 1.5 times better represented than in the population, while those under 35 were represented at only 0.5 to 0.8 of their proportion of the population. In other words, there is a higher abstention rate among the younger population. Of course, abstainers are not a homogenous group: they vary in their values and priorities, as well as in social position. If more people voted, both the Left and the far-right RN would probably benefit. However, the social and generational profile of people who voted in 2021 – and who are likely to do so in 2022 – tends to the right.

Are values shifting?

Voting patterns aside, have the values of French citizens moved to the right? According the 2021 ‘Fractures françaises’ poll, 42% of citizens were worried about crime levels and 34% about immigration, with both figures feeding into media debates. But there was little mention of the fact that 46% were concerned about the future of social security, 41% about protecting the environment, and 40% about the cost of living.

Similarly, when an October 2021 Harris Interactive survey found that 61% of respondents thought the ‘great replacement’ would ‘certainly’ or ‘probably’ happen, the media attention was considerable. That 77% of respondents said they were in favour of increasing the minimum wage to €1,800 gross per month was barely discussed.

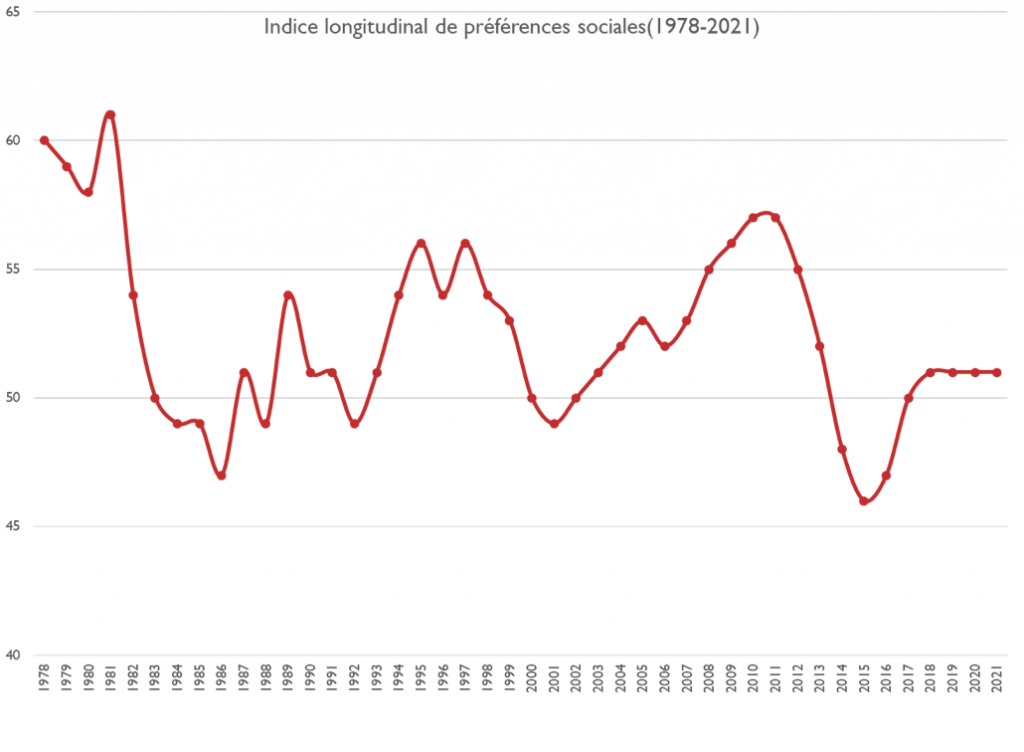

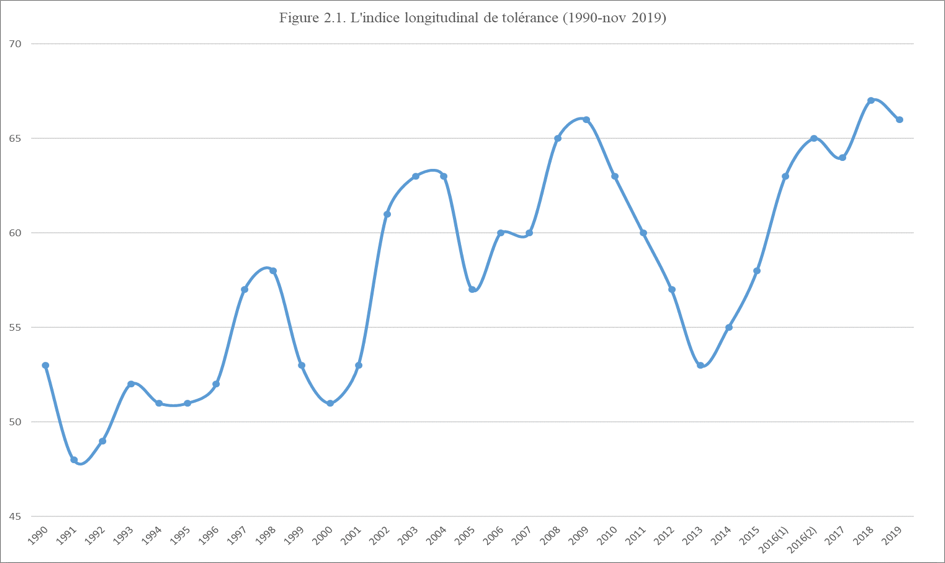

Most importantly, speaking of a shift to the right only makes sense diachronically. There needs to be a before and an after, and we need to be able to measure a change. Data covering France allows us to establish a longitudinal socioeconomic attitude index4 that aggregates a set of questions relating to redistribution, taxes, and the size of the state, i.e., socioeconomic issues, covering the period between 1978 and 2021. The racism barometer of the National Consultative Commission on Human Rights, meanwhile, enables us to create a longitudinal tolerance index compiling questions relating to immigration, xenophobia and attitudes toward minorities between 1990 and 2019.

Longitudinal socioeconomic attitude index (1978–2021). Note: 0 would mean that all respondents gave an economically liberal response for that year, 100 that all respondents gave a pro-redistribution response.

The first observation is that we are not clearly heading toward greater acceptance of economic liberalism. If this was the case, the figures would have reduced over time. Instead, they seem to go in cycles, with support for redistribution in the middle of the 1990s and between 2008 and 2012, and support for economic liberalism at the beginning of the 1980s and 2000s. Peaks and troughs in the index relate strongly to who is in power. In this respect, France changes in the same way as the USA, the UK or Canada: a rightwing or conservative government causes a rise in support for redistribution, and a leftwing majority produces support for economic liberalism.5

According to some analysts, François Hollande’s election was primarily motivated by a rejection of Nicolas Sarkozy’s personality and way of governing. However, the socioeconomic attitude index shows that the 2012 election occurred during an overall increase in support for redistribution that began in 2001, and which took this support to a level not seen since the end of the 1970s. What is more surprising is the significant drop in support for redistribution after the 2012 election. The index reached its lowest level in 2015, surpassing the previous low of 1986, even though François Mitterrand and François Hollande had very different aims for their socioeconomic policy. The socialist majority lost the ideological battle over ‘tax discontent’ without managing to put in place any major redistributive policies.

Emmanuel Macron’s period in office began in 2017 with an increase of four points in support for redistribution over two years – a typical change when the Right are in government – followed by a stabilization. This is certainly linked to the pandemic (in particular the ‘at any cost’ approach), but the balance can also be explained by internal tensions within the electorate on the issue of redistribution. The figures show a reduction in demands for state intervention in business and the private sector, as well as in social security contributions and taxes. At the same time, the French remain aware of the condition of the poorest and most precarious. It is therefore hard to conclude that socioeconomic attitudes have swung to the right. The most one could say is that there has been a polarization of opinion.

Longitudinal tolerance index 1990–Nov. 2019

The longitudinal tolerance index shows a medium-term trend towards openness to diversity. At the start of the 1990s, the index hovered around 50, while by the end of the 2010s, it was around 65. Three mechanisms explain this trajectory. First, the increasing proportion of the population with a university education, which is associated with a reduction in racism or xenophobia. Generational renewal also promotes tolerance, with older generations who are also the most conservative being replaced by the most open cohorts.6 Finally, current generations are more tolerant now than they were in the 1990s: people do not become more xenophobic as they age.

But along with this trend toward greater tolerance, there are also highs and lows linked to who is in power. Tolerance increases under rightwing governments, while there is an increase in xenophobia when the Left has a majority. Finally, specific events affect the index, such as the 2005 unrest in the suburbs. One might have feared that the 2015–2016 attacks would translate into an increase in intolerance, as in the United States after 9/11. This turned out not to be the case, because the political framing of the attacks avoided conflation with France’s Muslim community.

Calculation of the index was suspended in November 2019 because the face-to-face polling on which it is based was not possible due to the pandemic. There are concerns that xenophobia may have increased since then. However, the spring 2021 edition of the CNCDH barometer recorded a fall in xenophobia compared with 2019 across all indicators.

Last one standing?

In the medium term, it is therefore difficult to argue for a resurgence of the Right. At the most, there has been a balance since 2017, with a slight increase in favour of redistribution. The Left’s socioeconomic and cultural values were least popular in 2014–2015, but are now performing significantly better, even if the situation is far from the peak of 2011.

So why hasn’t this translated into voting intentions? In addition to the polling bias, the explanation can be found in an unprecedented degree of disconnect between citizens and the political parties/candidates. The existence of a crisis of confidence in politics first entered the discussion in the 1980s and since then its existence has become conventional wisdom. However, the 2010s saw a watershed.

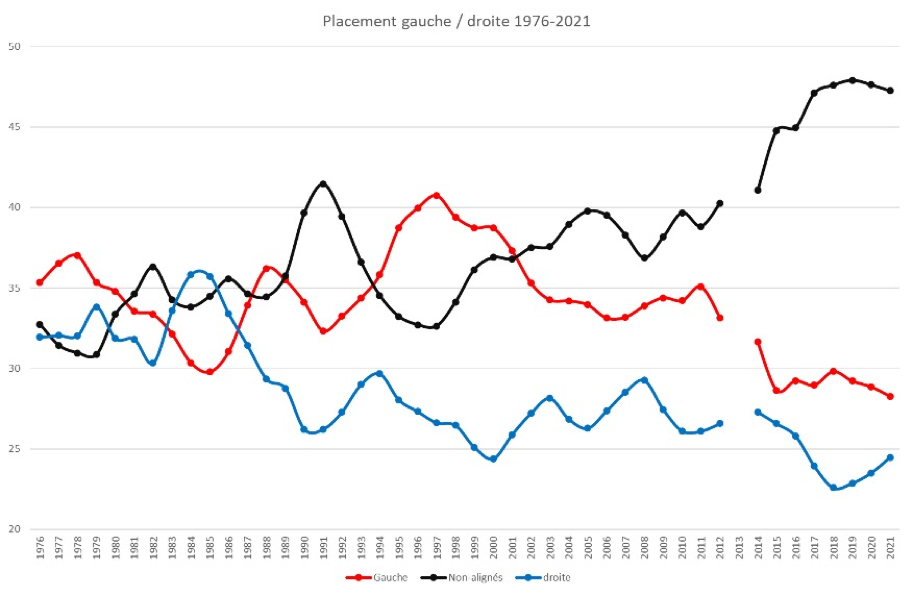

Right/Left alignment 1976–2021; red = Left; black = non-aligned; blue = Right

In the first few decades of the Fifth Republic, there was a minority of centrists among the ‘non-partisans’, while ‘le marais’ (the swamp) – i.e., citizens who lacked the cognitive abilities, knowledge, and feeling of legitimacy to align themselves politically – predominated.7 But the nature of these non-partisans changed in the 2010s and 2020s. They were no longer ‘ordinary citizens’: 26% of managers and upper-level professionals were nonaligned in 2012, rising to 36% in 2017. Less wealthy people have also joined this group from the left. In 2012, 36% of manual workers said they were on the left and 39% identified with the centre. From 2017 onward, just 26% remained on the left and the nonaligned reached almost 53%.

At the same time, the proportion of manual workers who identified as being on the right did not change. A similar pattern can be seen with white-collar workers. Could this be because ‘left’ and ‘right’ are now being replaced by new players and political movements – Emmanuel Macron and La République En Marche!, Marine Le Pen and Rassemblement National, Jean-Luc Mélenchon and La France Insoumise?

In the 2019 edition of the CNCDH barometer, a third of respondents said they were non-partisan, 20 points higher than in the 2000s. The younger the age bracket, the more affected it was by this phenomenon. Hence the 30% of baby boomers who were nonpartisan, compared with 36% or more of post-baby boomers and millennials. Support is weak for all parties. Just 9.5% of respondents supported La République En Marche!, which speaks volumes about Macron’s rule. However, Europe Écologie Les Verts with 13% and the Parti Socialiste or Rassemblement National with 10% are not far ahead.

When faced with this disconnect between citizens and the political parties, the Right fares better than the Left. Here, as with many other polls, we see that older generations, who lean to the right, are also the ones who vote most often and most consistently.

So why is there an impression of a rightward shift? There are three explanations, all of which are related. First, the polling landscape is more complex than we think and the ways in which we measure need to be altered. The move to the right in French society is perhaps more than anything a creation of our public debate, which focuses on some statistics while ignoring others. However, there is indeed a difference in levels of disengagement. While the centre, centre right and the far right are all affected by disengagement, in particular among the working class and younger voters, the Left is affected to an even greater extent.

Of course, those who choose not to participate bear the responsibility for that choice. However, if abstention levels are high at the next presidential election, the electors will not be representative of the country as a whole, and particularly not the lower classes and younger people. The higher abstention levels become, the more favourable the situation to Rassemblement National and perhaps Éric Zemmour.

Finally, there is the issue of the public debate, which has indeed shifted to the right. The ‘Fox-ization’ of CNEWS has led to a group of new conservatives being given a platform, able to influence the choice of topics as well as the manner in which they are discussed.8 A particularly striking example of this is Éric Zemmour’s campaign. His exceptionally high polling is in part because he has been able to benefit from exceptional levels of media coverage, without being challenged. Data provided by the Higher Audiovisual Council (Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel) shows that in October the BFM TV channel gave 26.5% of the airtime dedicated to official candidates to Éric Zemmour and 20.5% to Marine Le Pen, while Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Yannick Jadot and Anne Hidalgo put together received 19%. This imbalance is even worse on CNEWS: 51% for Zemmour, 13% for Le Pen, and 12% for the three main leftwing candidates.

The rightward shift of French society may still be an illusion. But unless we act against it, it may become reality.

Published in cooperation with CAIRN International Edition, translated and edited by Cadenza Academic Translations.

Luc Bronner, ’Dans la fabrique opaque des sondages,’ Le Monde, 4 November 2021.

Cluster 17, ‘Intentions de vote: Élections présidentielles 2022,’ Wave 3, October 2021.

See: Céline Braconnier and Jean-Yves Dormagen, La démocratie de l’abstention (Paris: Gallimard, 2007).

James A. Stimson, Cyrille Thiébaut, and Vincent Tiberj, ‘The evolution of policy attitudes in France,’ European Union Politics 13, no. 2 (2012): 293–316.

See: Christopher Wlezien, ‘The public as Thermostat: Dynamics of Preferences for Spending,’ American Journal of Political Science 39, no. 4 (1995): 981–1000.

Vincent Tiberj, ‘The wind of change. Face au racisme, le renouvellement générationnel,’ Esprit 11 (2020): 43–52.

Emeric Deutsch, Denis Lindon, and Pierre Weill, Les familles politiques aujourd’hui en France (Paris: Minuit, 1966).

Frédérique Matonti, Comment sommes-nous devenus réacs? (Paris: Fayard, 2021).

Published 16 March 2022

Original in French

Translated by

Cadenza Academic Translations

First published by Esprit 1-2/2022

Contributed by Esprit © Vincent Tiberj / Esprit / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.