Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine has put eastern Europe firmly at the centre of the EU’s foreign policy agenda and given fresh impetus to reforms by candidates for EU membership. But with rightwing movements gaining ground, support for Ukraine and EU enlargement is under threat.

Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing war have triggered a gradual shift in the European Union’s foreign and defence policy agenda. This policy shift comprises a reckoning of the EU’s limited capacity to deter military and hybrid attacks on its territory, and of an even less effective strategy to deploy the forces necessary to respond to possible attacks from an external aggressor, such as Russia.

To activate a stronger security and defence policy, European member states have so far accessed several tools. This European security toolbox includes a revitalised enlargement process further east, a collective commitment to support Ukraine’s war effort, increased military spending at national level, and more investment in the European defence industry. All these policies are reversible, yet the process of eastern enlargement remains the most challenging given the scale of the transformation required.

The countries in the EU’s Eastern Partnership have also adapted to post-invasion realities and shifted their foreign policy positions since the start of the Russia-Ukraine war and the EU’s growing interest in this previously largely neglected region. But varying perceptions of the threat from Russia have led to different policy outcomes. Some countries have made determined commitments to shift their security ties towards the West. Ukraine and Moldova have been most active in pursuing that realignment. Georgia’s political elites have also seized the opportunity presented by the EU’s openness to revitalise its enlargement policies and get closer to the EU, but continue to generate anti-liberal and anti-democratic practices that impede that European path.

Less definitively, but still worth noting, Armenia has loosened its ties to Russia, previously considered the South Caucasus nation’s ‘patron state’, partly in response to its lack of intervention in Azerbaijan’s takeover of Nagorno-Karabakh. Azerbaijan and Belarus have further autocratised, moving away from the institutions and democratic principles promoted by the collective West, which comprises the United States (US) and the EU. Belarus has moved firmly into Russia’s camp. In turn, Azerbaijan has improved its working relations with the Kremlin, while also increasing the volume of its energy exports to Europe, which replace those from Russia.

Policy alignment with the West in some of these Eastern European countries would not have been as notable in the absence of the security imperative generated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Yet not everyone agrees that Europe’s security is threatened by Russia or tied to further EU enlargement eastwards. The outcome of the European Parliament (EP) elections in June 2024 will deliver more Russia-friendly or Ukraine-neutral representatives in the EP and challenge the next European Commission to stay the course of solidarity with Ukraine.

Not least, the rise of the far right in national governments could put additional strains on Europe’s re-energised geopolitical ambitions and question its commitment to strengthen force projection. Importantly, any anti-European setbacks in candidate countries might also work against more support for the EU’s neighbourhood.

Ukraine

Of all eastern candidate states, Ukraine has received the most political, economic and military attention from the collective West. But EU governments and societies’ expectations of military victory and state reform accompanying such support have been far from realistic. This discrepancy will continue to affect the stabilisation and continuation of support for the war-torn country.

The military aid Ukraine received from European and NATO partners, while critical in preventing a total and immediate defeat, has proven insufficient and too slow to secure a Ukrainian victory. Slowly and predictably, this middling outcome has frustrated the European public, whose support for Ukraine has dropped on several key issues, including the provision of humanitarian aid and access to the labour market, the fast-tracking of EU membership, the sharing of energy costs, and the supply of military aid. In 2024, support only remains stable among Ukraine’s most loyal backers (such as the Nordic countries and the Baltic states), while it is ebbing among countries like Romania, Italy and Germany, and remains consistently low in nations such as Bulgaria and Slovakia.

In turn, Ukraine’s government and its people remain committed to their country’s European path. In February 2024, eight in ten Ukrainians were in favour of joining the EU and NATO. However, the reform task that accompanies EU accession negotiations requires an enormous effort from the Ukrainian government, which wartime conditions make even more difficult.

Since the European Council’s decision on 14 December 2023 to open accession negotiations with Ukraine, the country’s government has been hastening to align its legislation to the EU acquis. The government finalised its ‘Ukraine Plan’ for reform in spring 2024. But Ukraine’s agenda for EU membership remains a trying task for the embattled nation. The long war that lies ahead will continue to drain Ukraine’s human and financial resources and makes it difficult to build rule of law under martial law, which continues to curtail democratic freedoms, including freedom of movement, freedom of the press, freedom of peaceful assembly, and legal protections.

The European Commission is affording latitude in evaluating Ukraine’s (and Moldova’s) formal reform process. It also shows signs of understanding the daunting task ahead. To support Ukraine’s growth over the 2024–2027 period, the Commission has created a seemingly irreversible new instrument, the Ukraine Facility, to provide predictable financial support for Ukraine. But Russia’s persistent militarisation will prolong the war. This reduces the likelihood of being able to carry out major reforms that require ample human capital and state capacities: public administration reform; filling judicial vacancies and vetting sitting judges; building a credible track record of investigations, prosecutions and final court decisions in high-level corruption cases; and fighting organised crime, including controlling the illicit flow of firearms, human trafficking and cybercrime.

European political parties which already oppose more collaboration in Ukraine’s war effort will continue to weaponise the European public’s economic fears against more support for Ukraine. Far-right parties such as France’s National Rally, Hungary’s Fidesz, Germany’s Alternative for Germany, Romania’s Alliance for the Union of Romanians, or Slovakia’s Direction Social Democracy will create new obstacles to funding Ukraine’s war effort and impede progress on enlargement. In turn, funding delays and uncertainty about its European future will further frustrate Ukraine’s reform efforts.

Moldova

Moldova’s small size and economy makes it the easiest of all the eastern candidates to technically include into the EU’s single market. Yet the country is also one of the poorest in Europe and continues to have unresolved territorial issues in the largely pro-Russian breakaway region of Transnistria as well as in the autonomous region of Gagauzia, which is increasingly tied to Russia. Ethnic and territorial conflicts make the task of EU integration even more daunting.

According to a poll from early 2023, close to 60 percent of Moldovans want their country to join the EU, but Moldova’s European course depends on keeping pro-Russian forces out of the government. This latter goal requires a lot of political manoeuvring that includes limiting pro-Russian Transnistrians from increasing their influence on Chisinau politics.

The role of Transnistria – and increasingly, Gagauzia – is important in potentially affecting politics in Chisinau. In February 2024, the Transnistrian leadership asked Moscow to protect it from ‘increasing pressure’ from the Moldovan government.

Militarily, Russia does not invest attention or resources in Transnistria, a region with approximately 400,000 inhabitants, many of them pensioners. Moscow’s ambitions to destabilise Moldova go beyond Transnistria. In fact, many politicians in Chisinau fear that a too-rapid integration of Russian-speaking Transnistria into Moldova would actually be of far greater help to the Kremlin than leaving the region in this grey zone which has kept it free of violence since 1992. Similarly, most of the 135,000 Turkic but Russian-speaking Gagauz, are also backing pro-Russian parties.

Moldova will hold presidential elections on 20 October 2024 and parliamentary elections in 2025. To boost the chances of her pro-European party Action and Solidarity (PAS) and maintain her grip on the presidency, incumbent Maia Sandu has announced a consultative referendum for EU accession, to take place on the same day as the presidential elections. Polling as the first choice of 27 percent of voters, PAS is ten percentage points ahead of the pro-Russian Party of Socialists. Chance, Obligations, Achievements, another pro-Russian political bloc, ranks third. With ten percent of voter preferences, it could become the kingmaker in the second round of the presidential elections.

The Russian government sees the upcoming elections as an opportunity to gain more influence in Chisinau. Although Moscow maintains a foothold in Moldova through its grasp of pro-Russian Transnistria, there is no reason to expect it will escalate military conflict in this region. On paper, there should be 1,500 Russian soldiers in Transnistria, but according to Moldovan authorities, the majority are in fact locals in Russian uniforms. The number of Russian troops still on Transnistrian soil is in fact below 100 – not a number that represents a tangible military threat.

In addition, Ukraine has closed its border with Transnistria, indirectly providing protection from a land attack and cutting off legal and illegal trade. Although Transnistria’s leadership needs the connection with Russia to remain untethered from Chisinau, it is in its interest to also pursue economic integration with the Moldovan state. Since the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine war, the politicians and businessmen ruling Transnistria have stayed out of the conflict.

Just as in the case of Ukraine, work on preparing negotiation teams and the standardisation of Moldovan legislation, rules and procedures accelerated after the European Council opened accession negotiations with Moldova in December 2023. The process to harmonise Moldovan and EU legislation has been ongoing since 2018, but Moldovan bureaucracy’s capacity to deliver the changes required by the EU is limited. Its ability to negotiate better deals that won’t affect the Moldovan economy negatively in the long run is also restricted.

Georgia

Georgia officially pursues EU integration as its main foreign policy priority. In a poll from early 2023, 89 percent of Georgia’s population supported EU accession, while the ruling party Georgian Dream-Democratic Georgia (GD-DG) claims to have a pro-European agenda. Yet although the EU granted Georgia candidate member status in December 2023, Tbilisi is not pursuing reforms with the same determination as Moldova or Ukraine and is occasionally taking steps that distance the country from its EU path.

Most recently, a Russian-style ‘foreign agent law’ supported by GD-DG raised questions about the country’s commitment to EU values. Media organisations in Georgia fear that the law – requiring non-governmental organisations, activist groups, and independent media outlets that receive more than 20 percent of their funding from abroad to register as ‘foreign agents’ or face penalties – could be exploited to target journalists. Watchdogs see this decision as a way for GD-DG to accumulate more power ahead of the parliamentary elections in October 2024. In addition, recently proposed anti-LGBTQ+ laws that would prohibit people from changing their gender and ban same-sex couples from adopting children have also sparked criticism from western leaders.

Despite these measures, GD-DG still ranks first in public opinion polls, comfortably ahead of an unpopular and fragmented opposition. Despite the ongoing anti-government protests, the party is likely to secure first place in upcoming parliamentary elections, throwing Georgia’s pro-European path into further doubt.

GD-DG has also maintained an ambiguous position towards Russia and defends its friendly relationship with the country that occupied its provinces of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Georgia abstained from condemning Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, despite its own traumatic experience with Russia, which often uses Abkhazia and South Ossetia to destabilise Georgia and prevent its EU and NATO integration plans. At the same time, international evaluators, including the US and the IMF, confirmed that Georgia is nevertheless mostly aligned with the sanctions regime coordinated against Russia. Moreover, the EU remains Georgia’s main trade partner, with 20.5% of its trade, followed by Turkey (14.6%) and Russia (13%).

Protests against warming relations with Russia could continue and turn problematic for GD-DG and the country’s stability. But the government and GD-DG might also feel emboldened by weaker support for the opposition. Progress towards EU integration will remain slow as Georgia struggles to implement reforms.

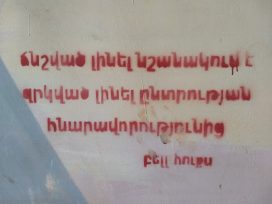

Armenia

In the last year, Armenia has given signals that it aims to improve its ties with the EU and move away from Russia for security guarantees. This change of foreign policy is the result of Russia’s failure to come to Armenia’s aid in Azerbaijan’s successful offensive in Nagorno-Karabakh in 2023. Russia’s passivity at Azerbaijan’s incorporation of Nagorno-Karabakh thus broke the mutual defence clause of the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO), a NATO-type intergovernmental military alliance consisting of Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Tajikistan.

Nikol Pashinyan, Armenia’s prime minister, has declared that Armenia’s membership in the CSTO is now frozen. Armenia also recalled the country’s CSTO representative, based in Moscow.

In the absence of any security guarantees from Russia, and willing to change the priorities of his country, Pashinyan appears to be focused on the formalisation of a peace treaty with Azerbaijan, even if this means ceding more territory in the form of four more villages demanded by the Azeri leadership. Pashinyan’s unwillingness to defend Nagorno-Karabakh from Azerbaijan’s military has nonetheless weakened his popularity, increasing the risk of instability.

Traditionally reliant on Russia for its arsenal, Armenia is now seeking to shift its security interests away from Russia and closer with the West. It has welcomed an EU mission to monitor its border with Azerbaijan, while aiming to purchase armoured vehicles and radar systems from France.

However, Armenia has also taken advantage of western economic sanctions against Russia. Armenian companies re-exporting western-manufactured goods such as cars, mobile phones, high tech-goods, and other consumer electronics have increased their business since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. Through this practice, Armenia’s overall exports to Russia have tripled. The higher taxes that these companies paid in Armenia also increased. Under strong pressure from the US and the EU to curb the re-export of hi-tech goods and components, Armenian exporters now need government permission to deliver microchips, transformers, video cameras, antennas and other electronic equipment to Russia.

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan further consolidated its status as an autocracy when incumbent president, Ilham Aliyev, won a fifth term on 7 February 2024 with more than 92 percent of the vote. Aliyev called for an early election after his successful capture of the Nagorno-Karabakh region in November 2023.

Since then, Aliyev has continued to improve relations with Middle Eastern and Central Asian countries, including the Taliban government in Afghanistan. His priority is to establish the Zangezur corridor, a customs-free transit route that would bisect Armenia’s Syunik region to connect Azerbaijan with its western exclave of Nakhchivan. Aliyev has been pressuring Armenia to agree to the concession of four villages that would bring him closer to this goal. The Azeri government has agreed the construction of the Zangezur corridor with Turkey, a necessary condition for speedy success.

Despite its increased autocratisation and renewed relations with Russia since 2022, the EU maintains close connections to Azerbaijan, primarily because of its oil and gas reserves and strategic location between Russia and China. The EU has been purchasing gas from Azerbaijan to reduce its reliance on Russia. At the same time, Azerbaijan has begun importing gas from Russia under a deal that should enable Baku to meet its own domestic demand.

Azerbaijan’s exports of natural gas to Europe have steadily risen from 2021 to 2023, reaching 19 billion cubic metres (bcm) in 2021, 22.6 bcm in 2022, and 23.8 bcm in 2023. The latter was divided between the EU, Georgian, Turkish and Serbian markets. However, Azerbaijan’s deal to import gas from Russia to enable Baku to meet its own domestic demand, calls into question whether the EU really has broken its reliance on Russian gas.

A fresh outbreak of war between Azerbaijan and Armenia continues to be a source of concern. While Armenia’s leadership is mostly accommodating of Azeri requests, some delays in the signing of the peace treaty and the renouncing of more territory that Azerbaijan wants could spark further conflict. The EU will likely remain only moderately involved in the region’s political intricacies and prioritise economic and energy concerns.

Belarus

As long as it stays under Alexander Lukashenko’s leadership, Belarus will remain irrevocably distanced from the EU. The bloc refused to acknowledge the legitimacy of Lukashenko’s presidency following the disputed election of 8 August 2020, which solidified his autocratic rule. Despite the widespread protests that followed, contesting his grip on power, Lukashenko remains firmly entrenched and has shown a willingness to employ any means of repression necessary to uphold his regime.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, partly from Belarusian territory, Belarus’s sanctions-hit economy has become increasingly more dependent on Russia. Although Belarus continues to stay formally out of the war in Ukraine, Lukashenko allows Russia to use Belarusian territory as a military base and staging ground for its armed forces. A document leaked from the Kremlin in 2021 showed concrete plans for an annexation of Belarus to the Russian Federation by 2030. Such a union would formalise existing arrangements but would require Russia to bear the added costs of ensuring the compliance of Belarusian society. Moscow has, however, already transferred tactical nuclear weapons to Belarusian territory.

Belarus’s weaponisation of refugees to create disorder on its borders with Lithuania, Latvia, and Poland has further damaged the country’s relations with its neighbours. Migrants travelling through Belarus and attempting to cross the EU’s borders will now have an even harder time finding refuge since the EU passed stricter asylum and migration rules in 2024. Latvia and Lithuania passed their own laws in 2023, formalising an ongoing practice of pushing back refugees at their borders with Belarus. According to the human rights organisation Doctors without Borders, many of those people who succeed in reaching Latvia, Lithuania and Poland still find themselves forced back into Belarusian territory by border authorities, frequently with the use of violence.

Conclusion

Political trends in some EU member states appear to be leaving Russian-friendly leaders such as Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban less isolated in his opposition to Ukraine. In France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Slovakia, and Romania, far-right parties are rising in the polls and could strengthen the anti-Ukraine stance in the European Parliament after the June 2024 elections and at the national level.

In this potentially more hostile environment for further solidarity with the EU’s eastern neighbourhood, any anti-European setbacks in candidate countries, such as Georgia becoming more politically aligned with Russia or an anti-EU government in Moldova, will fuel enlargement-scepticism. Given the strong link between EU enlargement and security, that outcome would prove detrimental for the EU’s force projection relative to Russia and limit its geopolitical ambitions.

Published 10 May 2024

Original in English

First published by Ukraine

© Veronica Anghel / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Flooded earth

Osteuropa 1–2/2023

What the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam means for water supplies, agriculture and industry in south-east Ukraine. Also: Azerbaijan’s ethnic cleansing in Nagorno-Karabakh; and a profile of imprisoned Russian oppositionist Vladimir Kara-Murza.

Since the Russian war on Ukraine, post-revolutionary Armenia has been turning towards the West in search of security. But how is the new situation impacting domestically on the vulnerable South Caucasus nation? Is Armenia’s democratic light in the region as bright as some would believe?