The fatal shooting of Michael Brown by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri on August 9th, 2014 led to the setting up of the “Black Lives Matter” movement in the United States. Part of the online backlash to this development was an assertion that millions of Irish had once been slaves, but that unlike black people they never complained about what had happened to their ancestors. As Fox News host Kimberley Guilfoyle put it in March 2016: “The Irish got over it. They don’t run around going ‘Irish Lives matter’.”

Such assertions were repeated hundreds of thousands of times and have appeared on millions of Facebook timelines. Assertions that large numbers of Irish migrants were once slaves came to be amplified in mainstream American and Irish media. What Liam Hogan has called the “Irish slaves meme” has been mobilised by the American alt-right, among others, to disavow legacies of racism and present-day racism while simultaneously promoting a white nationalist political agenda based on claims of white victimhood. Hogan has published several online articles aimed at understanding and debunking the “Irish slave” myth and has tirelessly challenged its reproduction in the mainstream media on both sides of the Atlantic. Such was his success that on March 16th, 2017 even the alt-right Breitbart news network published a fact-check article which unambiguously debunked the myth:

Reputable historians agree that the social media-driven reports deliberately conflate the extremely different contexts and conditions of African slavery and European indentured servitude. Analysts have noted that the reports gain particular traction among white supremacist sites and commentators seeking to downplay the evils of slavery.

The enslavement of Africans involved abductions, human sales at auctions and lifelong forced labour in a system that defined humans as property and trapped the children of those slaves in the same bondage.

Indentured servitude, while often accompanied by years of deprivation and exploitation, offered a usually voluntary means for impoverished British and Irish people to resettle in the Americas from the seventeenth to the early twentieth century. Contracts committed the servant to perform unpaid labour for a benefactor or employer for a fixed number of years in return for passage across the ocean, shelter and sustenance.

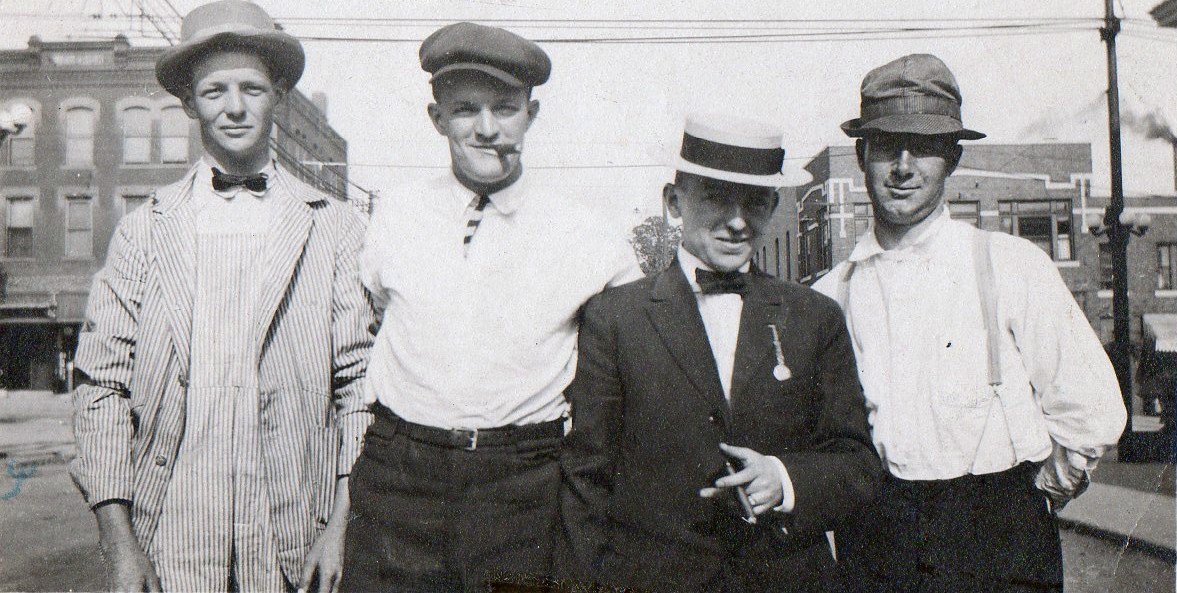

Irish immigrants in Kansas City, Missouri in c.1909. Source: WikiCommons

Breitbart reported that Irish-based historians had “decried the errors repeatedly to the point of exhaustion”. It stated that the myth of Irish slavery had sought to belittle the suffering visited on black slaves and had twisted existing records of Irish indentured servants “to lunatic effect”.

Yet anonymous Twitter hashtags such as #irishslaves, #realirish and #whitecargo continue to churn the “white Irish” slave meme. For example, @HibernoDiaspora urges her (by June 2017) 15,141 followers not to deny Hibernian slavery and the Hibernian Holocaust. Many of her postings, under the banner Hibernian Resistance, suggest that she is Irish but much of what she retweets endorses American, English and European white nationalistm; For example, @HibernoDiaspora retweeted posts describing the May 2017 Manchester bombing as an act of white genocide.

Fringe white supremacist groups such as Combat 18 and Stormfront have been going for decades. A Prohibition of Incitement to Hatred Act was introduced in the Republic of Ireland in 1989 to prohibit the printing of racist pamphlets by groups such the former. Stormfront, which pioneered the online dissemination of racist propaganda, began as a bulletin board for supporters of David Duke and had links to the Ku Klux Klan. Stormfront has long promoted an anti-immigrant white Irish nationalism alongside its equivalents in other countries. Its logo features a Celtic Cross and the motto “White Pride, World Wide”. The website supports sub-forums including For Stormfront Ladies Only and Stormfront Ireland. An analysis of Stormfront’s online activities undertaken in 2015 identified a total of 37,451 “White Nationalist Issues in Ireland” postings. Before the proliferation of social media this kind of content used to be fringe stuff or discreetly shared. A comparison with pornography is apposite. There is a lot of porn online but pornographic images are not openly shared with family, friends and work colleagues on Facebook or on Twitter millions of times.

Irish folklore and popular history have for centuries used analogies to and metaphors about slavery. Irish nationalism, as it developed among emigrants to the United States, was in many respects a white nationalism. The popularity of the “Irish slaves” meme cannot simply be blamed on the online propaganda of white supremacist groups. There are several elements at play beyond the deliberate falsification of the past. Widespread acceptance online of a false equivalence between chattel slavery and the treatment of Irish migrants appears to be rooted in Irish narratives of victimhood that continue to be articulated within Ireland’s cultural and political mainstreams.

There was little examination of slavery by white historians until the publication of Eric Williams’s Capitalism and Slavery in 1944. When it comes to examining the relationship between Irish migrants and slavery two books in particular stand out. These are Donald Akenson’s pioneering study of Irish slaveowners in Montserrat, If Ireland Ruled the World (1997), and Nini Rodgers’s Ireland, Slavery and Anti-slavery (2007). These examine how the Irish in English and Spanish colonies came to have much in common with other white European settlers. Some knew how to tap into Spanish patronage networks and how to propose new colonial ventures. In 1620 Bernard O’Brien, then only seventeen, was one of a company that set up a Gaelic-speaking tobacco colony on the Amazon. The Catholic Irishmen’s plantations were initially worked by native labourers but subsequently by slaves imported from Angola. In 1636 O’Brien applied for compensation to the Spanish king Philip IV for confiscation of his property including slaves and for permission to establish a further Irish colony on the Amazon.

While thousands of Irishmen and women were “Barbadosed” to work in tobacco or cane fields, Akenson details how some of these became slaveowners once their period of indenture had come to an end. Kristen Black and Jenny Shaw’s study of the Irish in the early modern Caribbean (published in the journal Past and Present in 2011) gives further examples. Records from 1656 note that Cornelius Bryan, an Irishman in Barbados, was sentenced to twenty-one lashes on his bare back as punishment for “a mutinous speech”. Thirty years later in his will he bequeathed “a mansion house”, twenty-two acres and “eleven negroes and their increase” – that is, any descendants of his slaves – to his wife, Margaret, and their six children.

Montserrat became the first place in the British empire where the Irish constituted a majority of white settlers. On arrival, many had worked as indentured labourers harvesting tobacco. By the time black slaves began to arrive in large numbers the Irish were no longer indentured and the main business became the harvesting of sugar. According to a 1672 census, Montserrat had a white population of 1,171 males of which some sixty-seven per cent were Irish. When women and children were added this came to a total of about 2,800. A large proportion of these had arrived from Ireland during the 1650s and 1660s. By 1678 the island had a population of between 1,500 and 2,250 slaves. By 1729 the Irish in Montserrat were, on average, bigger planters and owned more slaves than other white (British) settlers. Throughout the eighteenth century this white population did not increase by much. The majority were descended from Irish Catholics. However, the number of slaves on the island increased considerably. Montserrat contained 6,063 slaves in 1729 and had 9,834 slaves by 1775. The Irish on the island were part of a white Ascendancy. Montserrat, where the Irish owned thousands of African slaves, might seem to be an unusual case, but it should be borne in mind that Irish emigrants came to own slaves elsewhere in the Americas.

Liam Hogan’s online campaign against the “Irish slaves” meme included links to online registers of slaveowners with clearly Irish surnames who were compensated for the loss of their property in the Caribbean after the abolition of slavery there and in the United States after the defeat of the Confederacy. Some 539 Irish surnames were listed in an 1850 register of slaveowners in the United States. The number of slaves owned by those with such surnames rose from at least 99,129 in 1850 to 115,894 by 1860. Compensation records from 1834 for slaveowners in the West Indies identified 231 Irish surnames. These had owned 37,104 slaves. Many common Irish surnames were excluded from this analysis, including surnames that were also common in England and Scotland as well as Ulster-Scot surnames. The list of Irish slaveowners in the United States included the names of many Irish taoisigh (prime ministers) – Lynch, Haughey, FitzGerald, Ahern, Cowan and Kenny. It also included my own surname, Fanning. Some ninety-seven individual absentee slaveowners living in Ireland, who between them owned 15,869 slaves in British colonies, claimed compensation in 1834 when slavery was abolished. If you are of Catholic Irish descent the chances are your surname appears on one or other of these registers of slaveowners.

Most Irish-Americans, including post-Famine immigrants from Ireland, came to oppose the abolition of slavery. The reasons why and the legacies of Irish anti-abolitionism are also part of the back story of twenty-first century white Irish nationalism. Noel Ignatiev, in the much-cited How the Irish Became White (1995), argued that the Irish used racism towards African-Americans as a tool to reposition themselves as white. But they were never black to begin with. Examples given by Ignatiev suggest that many Irish immigrants viewed themselves from the start as racially superior to African-Americans. He describes complaints made by Irish immigrants fresh off the boat in Boston that coloured people did not know their place.

The Catholic Irish found themselves near the bottom of a hierarchy that recalled the one they left behind in Ireland. As put by Steve Garner, the social system within which Catholics in the United States found themselves after the Famine echoed the one that they left. They were depicted as inferior to Protestant Americans, and to the Scots Irish, many of whom were descended from earlier waves of migration from Ireland. But in the United States they were not at the bottom of the prevailing hierarchy. They were white citizens in a country that refused citizenship rights to either African-Americans or non-white immigrants. For all that they came to use the term race to denote their own ethnic identity, they were white, and part of the same race as other white Americans and white subjects of the British empire.

There were pragmatic reasons why Irish emigrants and Irish nationalists at home looking for support from the United States might oppose abolitionism, or at least stay out of the debate. However, during the decade before the Civil War many Irish-Americans were apparently hostile to all shades of anti-slavery. Historians have variously explained this as due to immigrants’ fears about having to compete with African-Americans for employment and because of their attachment to the pro-slavery Democratic Party. In an essay entitled “The Transatlantic Roots of Irish American Anti-Abolitionism, 1843-1859”, Ian Delahanty argues that pro-slavery was not just a stance aimed at benefiting the Irish in the United States. It became integral from the late 1840s to the politics of Irish nationalism. Young Ireland émigrés established several newspapers, and while these expressed a range of opinions they were united in their opposition to the abolition of slavery. In the New York Nation on August 4th, 1849, its founder, Thomas D’Arcy McGee excoriated O’Connellite abolitionists in the following terms: “Their task is to liberate their slaves, not to travel across the Atlantic for foreign objects of sympathy.” McGee first came to prominence for a speech he gave in Boston aged seventeen in 1842, not long after he arrived from Ireland whose people, he told his audience, “are born slaves, and bred into slavery from the cradle; they know not what freedom is”.

The pro-slavery argument was promoted most trenchantly by the Young Ireland polemicist John Mitchel. Taking the position that his enemy’s enemy was his friend, Mitchel approved of the South’s slave-owning economy because it rejected the liberal capitalist system that had come to dominate the British empire and much of the United States. The Southern secessionists, Mitchel believed, best exemplified an equivalent opposition in America to the economic system that had come to dominate Ireland with O’Connell’s blessing and which Mitchel, writing as an émigré, blamed for the Famine. Slavery had to be defended because abolitionism was the ideological jewel of the system of ideas that according to Mitchel had devastated Ireland and killed or exiled millions of its people. On September 23rd, 1854, for example, in The Citizen, a newspaper he founded in New York, Mitchel argued that the slave trade with Africa should be reopened and that the “ignorant and brutal negroes” would enjoy “comparative happiness and dignity” as plantation hands. Ironically, for all his advocacy of slavery in America, Mitchel came to be revered by many Irish nationalists for his excoriating criticisms of anti-Irish racism. His anti-colonial critique of British liberalism had considerable influence on later generations of Irish nationalists.

Similar stances to those identified by pro-slavery Irish-Americans and anti-abolitionist Irish nationalists also found expression in subsequent writings about the place of Ireland and the Irish within the British empire. The argument that Ireland deserved to be a free nation because the Irish, unlike many colonised peoples in the British empire, were white men, was forcefully expressed by Erskine Childers, a veteran of the Boer war. As argued by Childers, it was the whiteness of the Irish that gave them their right to self-government.

He outlined this argument detail in his 1912 book The Form and Purpose of Home Rule. In a chapter entitled “Revolution in America and Ireland” he argued that there must be a radical difference between the government of places settled and populated by white colonists and of places merely exploited by white traders. In a chapter comparing South Africa and Ireland he attacked the abolitionist movement, using similar arguments and phrases to those employed more than half a century earlier by Mitchel and McGee. Abolitionists, he declared, had absolutely ignored the economic serfdom of the half-starved Irish peasantry.

The case developed by Childers echoed one made by the Afrikaner leader Jan Smuts. Both insisted on the need for racial equality among white peoples. Childers had served as a volunteer in a British artillery company in South Africa. Although he fought against the Boers he sympathised with their efforts to maintain white prestige. He argued that Ireland deserved parity with the white colonial nations and should identify “her own destiny now and forever with that of the British empire”. As he put in The Form and Purpose of Home Rule:

She has helped build that Empire; it is bone of her bone and flesh of her flesh. Far and wide throughout its scattered dominions her sons are joining in the appeal to justice for the country which is home to their race, and longing to see Ireland take her place as a contented and above all a responsible member of the Imperial family.

While this sentiment was hugely at odds with the anti-Britishness of Irish-America and with separatist nationalism, it was consistent with the political stakes as perceived by Irish-Americans, with their claims to white entitlement and with their anti-abolitionism. Childers argued that the Irish had helped to build the British empire and deserved their share just as Irish immigrants wanted a place in an American manifest destiny that did not include natives and non-whites. Childers’s obsession with whiteness made him unusual among Irish nationalists, even if his claims to white entitlement were hardly unique. For example, Arthur Griffith, in his preface to the 1913 edition of John Mitchel’s Jail Journal, insisted that no excuses were needed for an Irish Nationalist declining to hold the Negro his peer in right.

A capricious use of analogy – asserting that the Irish were treated “like slaves” – permeates centuries of writing about Irish history. Long before postmodernism and its associated relativisms, slavery was whatever you felt it was – a feeling rather than a particular system. There has long been a tendency among Irish writers to describe the colonisation of Ireland and the subjugation of the Irish as a form of slavery or analogous to slavery. In this context popular books such as Sean O’Callaghan’s To Hell or Barbados: The Ethnic Cleansing of Ireland (2000) repeatedly described voluntary indenture, practices of tricking people into signing indenture contracts, economic pressures that led poor people to sign such contracts, as well as press-ganging and forced transportation, as slavery. Although O’Callaghan’s book ignored academic scholarship like Akenson’s, it felt right. Not alt-right, not far-right ‑ but in keeping with the general tone of anti-colonial writing from an Irish perspective.

There is a significant body of writing about Ireland’s history by scholars who draw upon postcolonial theory, which promotes equivalence between Irish experiences of colonialism and that experienced elsewhere in the British empire. It is perhaps in this context that O’Callaghan’s claim that the Irish were enslaved in the Caribbean was cited uncritically in Bill Rolston and Michael Shannon’s seminal Encounters: How Racism Came to Ireland (2002) alongside a succinct account of Ireland’s involvement in the Atlantic slave trade. During the nineteenth century some African-American intellectuals drew inspiration from Catholic emancipation in Ireland (from institutionalised religious discrimination) in making the case against chattel slavery in the United States. African-American opponents of chattel slavery such as Frederick Douglass toured Ireland and found some support for their cause among supporters of Daniel O’Connell. Expressions of anti-colonial solidarity in both directions were genuine. Independence and anti-colonial movements in India and Palestine and the anti-Apartheid movement in South Africa drew some inspiration from Irish independence movements. Nationalists in Northern Ireland have, in turn, promoted equivalences between their struggles and anti-colonial ones. In recent decades, Palestinian flags have been flown in Catholic areas of Northern Ireland. Gerry Adams, who had repeatedly drawn analogies between the Northern Ireland peace process and the post-Apartheid transition in South Africa, was chosen to be part of Nelson Mandela’s funeral honour guard.

Yet Adams also endorsed the “Irish slaves” myth in a May 2016 radio interview. A few evenings earlier on Sunday, May 1st, he had tweeted: “Watching Django Unchained, A Ballymurphy Nigger”. In his response, two days later on the Ryan Tubridy radio show, to the minor controversy that followed – during which he was mostly criticised for his use of the N word – Adams offered the following explanation: “I was paralleling the experiences of the Irish, not just in recent times, although from the sixties onwards; there are lots of parallels, going back to our own history, the penal days, when the Irish were sold as slaves through the Cromwellian period.”

At a time when white nationalism has found expression within the political mainstream of several European countries as well as in the United States, the absence of equivalent rhetoric in the Irish case stands out. During the post-2008 austerity period no Irish politician called for “Irish jobs for Irish people”, whereas such postures were struck even by mainstream political leaders like Gordon Brown in the United Kingdom. At the same time immigrants and ethnic minorities in Ireland experience the same kinds of racism as their equivalents in other European countries. Anti-immigrant nativism has not found expression to date in mainstream politics in the Irish case. But narratives which represent the Irish as having been slaves are hardly harmless. From the 1840s onwards racism was pressed into the service of Irish nationalism. This white Irish nationalism came to be conveniently forgotten within subsequent mainstream nationalist narratives and with the foregrounding of symbolic political alliances which emphasised solidarities between the Irish and the mostly black peoples of the former British empire. These are perhaps useful narratives when it comes to arguing against racism. Yet versions of Irish history which obfuscate past Irish racisms have proven to be a toxic export and may well exert future malign influence on Irish politics and society.